- Home

- Subhash Chandran

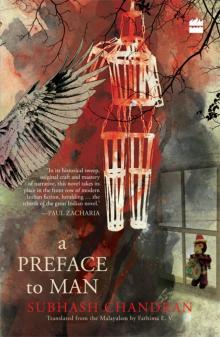

A Preface to Man

A Preface to Man Read online

a

PREFACE

to MAN

SUBHASH CHANDRAN

Translated from the Malayalam by Fathima E.V.

NEW YORK • LONDON • TORONTO • SYDNEY • NEW DELHI

For those who were born in the last century

and are living in this century

‘If a human child, who is born fearless, independent, and above all, creative, ends up craven and bonded in sixty or seventy years, spending his creativity solely for procreation, and finally dies as a grown-up child in the guise of an old man, and if this is called human life, my beloved girl, I have nothing to be proud of in being born as a man.’

—from a letter Jithendran sent to Ann Marie

Contents

Prologue

Part One – Dharmam

1. The Address

2. Ancestors

3. Thachanakkara

4. Glorious Mother

5. Two Kinds of Rivers

6. Casteism

7. The Vortex

8. The Outsider

9. Crepe Jasmine

10. The Circle

Part Two – Artha

1. Transformation

2. Seed

3. The Decade

4. Siam Weed

5. Meanie

6. Crescent

7. The Birth

8. Progeny

9. Iconoclasm

10. Treasure Chest

Part Three – Kama

1. The Sequel

2. Maternal Uncle

3. Mixed Breed

4. The Well

5. The Old Man

6. Oxen

7. Caterpillar

8. Maelstrom

9. Harbinger of Death

10. Swayamvaram

Part Four – Moksha

1. Portal

2. Darkness

3. Fragmentation

4. The Embodied

5. Omnivore

6. Odds

7. Religious Rivalry

8. Creation Song

9. Abandonment

10. Zenith

Epilogue

Glossary

PS Section

Acknowledgements

About the Book

About the Author

Praise

Copyright

Prologue

‘Man is the only creature that perishes before attaining full growth!’

It was in his fifty-fourth year, while listening to music with his wife in their eighth-floor flat in the massive building that had recently sprung up on the ground where he had played cricket as a child, that the pain that began as a tickle in his lower abdomen rushed to his heart. Bewildered at not being able to enjoy the beautiful violin rendition between the anupallavi and charanam, he remarked thus and, rather involuntarily, died.

Except for a recent swelling in the prostate gland, he had had few illnesses to speak of. Since he had reached a stage of incontinence where he was emptying his bladder too often, he had just started inserting baby diapers into his underwear. Whenever his wife suggested adult diapers, he stopped her.

‘Not those,’ he had said, laughing. ‘If we buy those, the shopkeeper will know that one of us is peeing in our clothes. Even more shameful would be him coming to know that we are getting old.’

Therefore, pretending it was for their grandchildren, who were coming to celebrate Onam and his birthday with them, she bought baby diapers and multi-coloured plastic flowers. He began to leak away into them secretly, regardless of day or night. In his childhood, such disposable nappies were not available in the local market. Though the word ‘readymade’ had already entered common commercial parlance, it had seldom been used in connection with menstrual or nappy cloths. By the time diapers began to appear in local shops during the last decades of the twentieth century, he had turned a young man.

When his children were toddlers, old cloths were deemed good enough to stem the flow of all effluents from urine to blood, thanks to his wife’s reluctance to give up her habit of thrift, ingrained in her while living through lean times. This meant his children were not fated to use store-bought diapers. As was the case with many things in his lineage, the fortune of using readymade diapers for the first time befell him, even though at a rather late stage. Standing without embarrassment in his baby diaper in front of his wife, as if to gauge the acuity of his yet fecund powers of self-deprecation, he declared, ‘See, the urinembodiment of manliness!’

In the extended history of mankind, he was of the generation that had used many things for the first time. In the years of his adolescence and youth, children were effortlessly handling gadgets that their parents could not have imagined even as late as the last decades of the twentieth century. Televisions with remote control; mobile phones; computers with their endless possibilities; mammoth apartment buildings that ensured one had neighbours not only on four sides but also above and below; mechanized domestic appliances from brooms to coconut graters; prophylactics that titillated—those were the miracle years when all these were like newborn animals springing to their feet as soon as they were delivered. His was also the last generation of children who found happiness in simple toys made by inserting the spines of coconut leaves into the spongy centres of small, unripe coconuts thrown down liberally by coconut palms.

Now, a bittersweet smile in remembrance of those things played on his lips as he lay on the sofa, dead. Noticing the frozen smile, she shook him by his shoulders and asked, with more alarm than sadness in her throat, ‘Gone?’

To prevent others from seeing how those unusually melancholic, large eyes that had remained wide open for fifty-four years were beginning to wilt like dying flowers, she pressed them shut with trembling fingers. Then, switching off the music player gifted by their eldest daughter on his birthday two weeks ago, and which had started playing only moments ago, she got up and phoned next door. ‘Yes,’ she told her disbelieving neighbour, in a voice that hid the tears, ‘please inform everyone. Here he is, sitting serenely on the sofa!’

In those moments, she hoped that she was caught in a bad dream. He was still sitting on the sofa in the living room, resting on huge yellow pillows, with his pale blue lungi folded above the knee, a cashew nut trapped in his curled right palm. Next to him, on the floor, was a glass with only a sip of rum left, still mixed with one of his last breaths. She quickly removed the glass and the bowl of cashew to the kitchen, so that the visitors would not take him to be a drunkard. His shirtless body leaned to the left when she pulled out one of the pillows. Unable to bear the weight of the hapless head, the neck stretched like the stalk of a flower. With the help of the two women and an old man, who were the first to reach, she laid him out on the sofa and pulled down the lungi that had come undone, to cover his thighs and knees.

Then she noticed that his skin was a mass of goose pimples and his nipples were erect from the enticing touch of death.

That was on a wet evening in the month of September, two thousand and twenty-six. The prime minister, who was almost his age, had had two terms in power and was now in hospital in critical condition, after an attempt on his life was made while he was campaigning for another stint. Bored by all ninety-eight channels airing only this news, he had switched off the TV and decided to listen to some music. After its thermocol packing was removed, the new music system came into his life like a newborn separated from the placenta and freshly bathed, their lives intersecting for only a few moments. With his eyes shut, and as if picking lots, he had taken out a disc from the crammed cardboard box with its astonishing array of music from his youth. Film songs of the twentieth century that people had more or less forgotten. It was when he was reading the titles of the songs from the fading covers of the long-negl

ected discs that he began to experience the mild pain that had initially felt pleasurable, like a tickle in his lower abdomen. With his right hand pulling into place the tiny diaper that had begun to slip from its position inside his underwear he had walked into the kitchen. When he could not decide which bottle of alcohol to choose from the upper shelf, he decided to pick that too through lots. There were two or three varieties, though he was only an occasional drinker. Taking care not to topple the bottles over, he had closed his eyes, extended his hand, and picked one at random. In that bottle, left unopened for years, was an excellent rum, darker than black tea. When the top of the bottle was snapped open as in a post-mortem, the joy of his youth bubbled up along with the smell of sugarcane and caramelized sugar, and reliving it, he had come out to the living room carrying the glass, water, and cashew nuts. He had called out to his wife, who was on her way to the balcony at the back with her spectacles and newspaper as usual. He made her sit next to him and started the music, after blowing the dust off the disc. Watching the September rain weaving threads in the eighth-floor sky, as the singer stretched his ‘O…’ through three levels on lower octaves before uttering the invocation to the enticing ‘kaattu chembakam’, and feeling the tickle in his stomach getting heavier and rolling up, he had exclaimed to his wife: ‘Our A.M. Raja!’

Because it was a second Saturday, as soon as the news got out, the neighbours crowded around the body in the seventeen-by-twelve-foot hall. Though there were five doctors living in that apartment building, not one was able to reach on time to confirm the death, because of their busy schedules. Finally, a dentist, who had recently moved onto the thirteenth floor, was summoned. Having been brought up as the darling of indulgent parents, he had not quite acquired the necessary edification in matters in which grown men are well versed—such as alcohol and death. When he bent over the body and lifted up the eyelid with his thumb to check the pupils, he was assailed by fumes of rum from the open mouth; he also spotted the crooked tooth in the lower row. Smelling the mouth of a corpse for the first time, and trying to hide his confusion at not recognizing the smell of rum, with unwarranted foreboding, he declared in English: ‘Before it starts reeking further, let’s begin the funeral rites!’

Some people moved the chairs and the large cane teapoy aside. The dining table was carefully placed with its glass top facing the wall, and its pointed legs were swaddled with worn towels and a soiled mundu. It was the first death among the twenty-eight families living in the new building. Neighbours took charge of the preparations as if training for future deaths that were liable to occur in their houses as well. By then, the undertakers too had arrived.

Though their charges were rather high, they were acclaimed for beautifying corpses and making them appear better looking than during their lifetime. After the dead man was shaved and stripped naked for his bath, they laughed, spotting the diaper with the image of a coy duck on it, forgetting that it was on the genitals of a corpse. Still, even the neighbours did not realize the diaper had been bought specifically for him, and took it as something of an accident that he had had on him one of the baby clothes left behind by his grandchildren.

She resented being stuck in the midst of women in the inner room, which prevented her from watching the proceedings, while others lifted and placed on the floor his tall, slim body, now bathed and sheathed in white, a body that she alone had held in power for twenty-six years since their wedding. As she deftly flung his brown underwear under the bed, yanking it from the bedpost on which it had been deposited lazily the previous night, she could not help habitually muttering, under her breath, the usual admonishments: ‘Damn! What would people think if they were to see?’

The truth was that, for some time, she could not assimilate the fact that she had been newly elevated to the role of a widow. Initially, she smiled warmly at each person who had walked in after paying respects to the body laid out in the front room. Many a time, she almost asked them to be seated and nearly offered them tea with the practised ease of hospitality. Only when the bitter odour of something that had been rendered vacuous wafted into the bedroom, along with the aroma of the incense sticks that had wafted listlessly in the cramped flat, did it finally dawn on her that she was a bereaved housewife.

However, the man who had died with a child’s diaper on him was floating like a leaf on an ocean of comprehension far greater than hers.

A quarter of a century ago in another place, at the fag-end of a honeymoon, and yearning for an offspring at the age of twenty-eight, he had had his first unprotected intercourse in a bed in a rented house still stained with filthy water from the sewers and shit overflowing the septic tank. Having finally decided to submit himself completely to an average life with no claims to anything extraordinary, his life was split into two equal parts: the first half was that of a soul that had burnt away, having failed to find a medium for realizing something he firmly believed would light up the lives of his fellow human beings, despite once believing he had the power to do so, based on a number of assumptions accumulated since childhood about the greatness of man. The second half was comparatively simpler: the unduly serious continuance of a job that least bewailed the wastage of a lifetime; a wedding that began in debt and a marriage that continued in debt; one or two changes of residence accompanied by small lorries stuffed with household things; property partitions accomplished by hating one’s siblings, being hated by them in turn and making God laugh; two or three liaisons with other women, attempted purely for the ineffable joy of indulging in forbidden transgressions, and with no carnal pleasure derived; some loud mirth here and there; tiny, inconsequential hurts that friends and relatives had handed out like gifts; accusations and offences that could hardly be blamed on circumstances; quantities of medicines swallowed for illnesses that would have healed on their own; the two or three occasions in life when he had had to endure the tedium of acting responsibly, dictated by auspicious times.

Yes. A pitiful body that would have crawled through so many commonplace situations that even a novice of a fortune-teller could have read similar occurrences on anyone’s palm—and could have predicted that he would, one day, die unsung.

Until their two children and their families—who must have cursed him for making them return after a gap of only fifteen days—arrived early next morning, the body lay preserved in a refrigerated display box. The service lift for transporting heavy objects had been under repair for the past week. Hence, when the freezer came late that evening, it had to be hauled up the stairs to the eighth floor and brought down the same way the following day. The funeral being on Sunday, a few more of his relatives had arrived. The corpse had to be taken down in the small passenger lift to the ground floor, inviting frowns from the other inhabitants. During the attempt to take him down from the eighth floor, and because the lift was too small to keep the white-swathed body horizontal, once again with the help of others, it had to be propped up vertically, and for one last time it stood upright on the ground. The exertion of the pranan to hold upright a seventy-four kilo body was registered with a shudder by people who weighed more.

Nevertheless, the fifty-four-year-old body that burnt down pliantly that Sunday in the suburban Electric Crematorium for Nairs, was only the second half of his life. The first half had conclusively ended in a moment in his twenty-eighth year, when he had failed, after admitting that it is impossible for man to attain his full potential and that the only thing possible would be a helpless splitting into the next generation. Yet, in those first twenty-eight years, he felt the leaden and invisible burden of at least five generations that had preceded him and who stood with their feet planted on his soul.

Rain kept pattering down. That man, who had been born centuries before his birth, had actually died much before his own death.

His name was Jithendran. He was a Malayali.

Part One

Dharma

All that is known variously as the one and the other,

When considered, is but the prim

al self-form of the world.

All that is done for the delight of the self

Ought to bring happiness to others as well.

—Sree Narayana Guru (Aatmopadeshashatakam)

ONE

The Address

It was on her first day of widowhood, after the funeral, alone in the flat bereft of kith and kin, that she rediscovered a whole trove of words that she alone had believed to be priceless, though her husband had, a quarter of a century ago, discarded them with pained contempt. They were a collection of letters and the summarized outline of a novel he had yearned to write in his youth. She had once salvaged it from a pile of books sodden from the gutter water gushing into their house, and had put it away with care after drying. There were the forty, many-hued letters he had written to her in the final ten months—between March 1999 to January 2000—of the interminable six years that had felt as long drawn out as the lifespan of the ageless Manu, starting from the day she was chosen to be his wife and extending to their wedding day. Most of those letters were replete with words that reeked of love—not much different from the kind any lover would write to his woman. While reading them in those days used to make her heart and fingers tremble, now, in her fiftieth year, she could return to them unaffected, as if they were written by an unknown man for an unknown woman. But reading them now, she was distressed as never before, confronted by this chronicle of the persistent anxieties about the dignity of individuals who had tormented him even at that young age, and who kept cropping up every now and then in his letters. She read and reread those sentences that were unlikely to be written again by any young man to any beloved or any friend. With a wildly palpitating heart, she read those parts of the novel that he had abandoned unwritten in his twenty-eighth year.

She felt that the angst that had tormented him while writing still seemed to lurk in them, despite the passage of a quarter of a century. Her fingers burnt when she ran them over the letters. They began to swell and grow inside her like the seeds of lofty trees conserved for the future. She had had no right to access them for a quarter century. He had shown incredible aplomb in being at peace with himself, without talking or thinking about them. Whenever she had reminded him of those summarized notes that could have blossomed into a novel, he laughed them off, as if they were someone else’s life. It was one of those rare instances when he had laughed his open-mouthed, hearty laugh. But now she had all the time, the rest of her life in the helpless loneliness of her widowhood, to reflect again and again and to transform those word-seeds, dear to no one else, into gigantic trees and dense forests.

A Preface to Man

A Preface to Man